-

Graduate of Central Saint Martins, UAL. Former head of design at BCG Digital Ventures, having worked at Panasonic Design Company, at PDD Innovation as creative lead, and at Ideo Tokyo as a founding member and design director. Extensive experience in innovation projects. Jury member for D&AD, Good Design Award, and other programs. Author of Hello, Design: Design and the Japanese People (NewsPicks Book).

-

Visiting Professor at Kyoto University of Art & Design. Graduate of the University of Tokyo. Before joining Airbnb Japan in September 2016, served as a strategic consultant at IBM Business Consulting Services and PwC Advisory in new city/region-focused business strategy and service design in smart cities, infrastructure export, MICE strategy, and other applications. Managing officer at Airbnb Japan since 2017. Author of Professional Meeting and other publications.

-

Director of the NPO Arts and Law, and co-director of Creative Commons Japan. Senior researcher, Keio University Research Institute at SFC. Engaged in hands-on legal service and advanced/strategic law for new business and strategic planning by startups and large companies alike, in IT, creative, and urban development fields. Administrative and municipal committee member and advisor. Author of publications including Legal Design: Accelerating Creativity and Innovation through Law, and Open Design Now: Why Design Cannot Remain Exclusive (joint translation/writing).

-

Principal architect of OnDesign, which practices open, impartial design for buildings of all kinds by encouraging client creativity through dialogue. Winner, JIA Young Architect Award/jury award as a special entry at the Japan Pavilion, Venice Biennale (Yokohama Apartment), Disaster Recovery Design and Community Recovery Award (Ishinomaki 2.0). Other noted work includes a study center in rural Ama, Shimane (Okinokuni Learning Center). Author of Open Architecture and Experiments from OnDesign.

-

Visiting Associate Professor, Kyushu University. Former McKinsey management consultant with experience in Japan, the U.S., and Europe. Established a youth leadership foundation supporting Tohoku recovery. Special correspondent for Wired covering North America. Helped establish the MEXT public-private Study Abroad Initiative program as project officer. Became a founding member of Quantum, leading joint business development for both startups and large corporations.

-

Graduate of Yokohama National University. Founded Keiji Ashizawa Design in 2005 after experience at Architecture Workshop and the furniture studio Super Robot. A collaborator with international furniture brands including Ikea and electronics manufacturers in Japan, and a participant in architectural projects and workshops around the world. Established Ishinomaki Laboratory in 2011 as a public workshop promoting disaster recovery through furniture production and DIY projects.

-

CEO of Nosigner. Guest associate professor, Graduate School of SDM, Keio University. Active in design intended to drive society forward, through social design applying interdisciplinary expertise in fields including architectural, graphic, and product design. Jury member in many design award programs and recipient of more than 100 top awards around the world. Advocates evolutionary thinking for insight on socially transformative ideas, drawing on comparisons between biological evolution and design.

Founding Partner / AnyProjects inc

Shunsuke Ishikawa

An era when we should question basic assumptions

One senses that in this era, companies or organizations attempting to create new value should begin by asking questions. Imagine the process of designing an office. Logical approaches—such as quantifying productivity based on the minimum space per person—often only lead to the same kinds of solutions. The office may end up being efficient, but this approach prevents us from offering fresh experiences or creative value. Skilled designers take a different approach. Their thinking begins with questions: What's working all about, anyway? or What latent needs do we have about where we work? This trait of good designers is what society itself needs today.

In creating new value, another consideration also seems essential. As I will explain, it involves what I call "kind technology." Accelerating progress in AI and robotics has led to much speculation about dystopias where these technologies steal our jobs, but is this inevitable?

Technology has also enabled individuals to create goods and services more easily in response to their own questions. Many goods and services are being produced, but to earn people's support, they must be thoughtful. Like the cartoon character Doraemon, they will help and support us when we have problems. The expressions of technology sought in times to come will address our emotional well-being, as things that are not just convenient, but that we can lean on, that sometimes give us spirited encouragement for growth, without leading us astray. As an alternative to dystopia, "kind technology" thinking draws on this Japanese sensibility behind Doraemon to frame our future engagement with technology in a way worth sharing with the world.

Enabling technologies

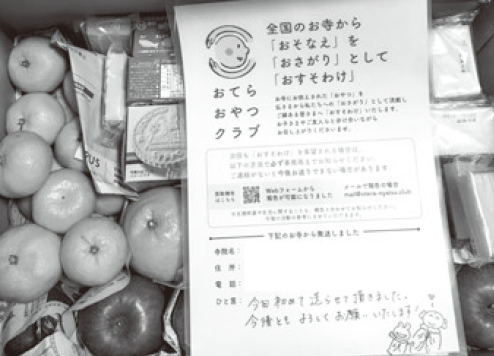

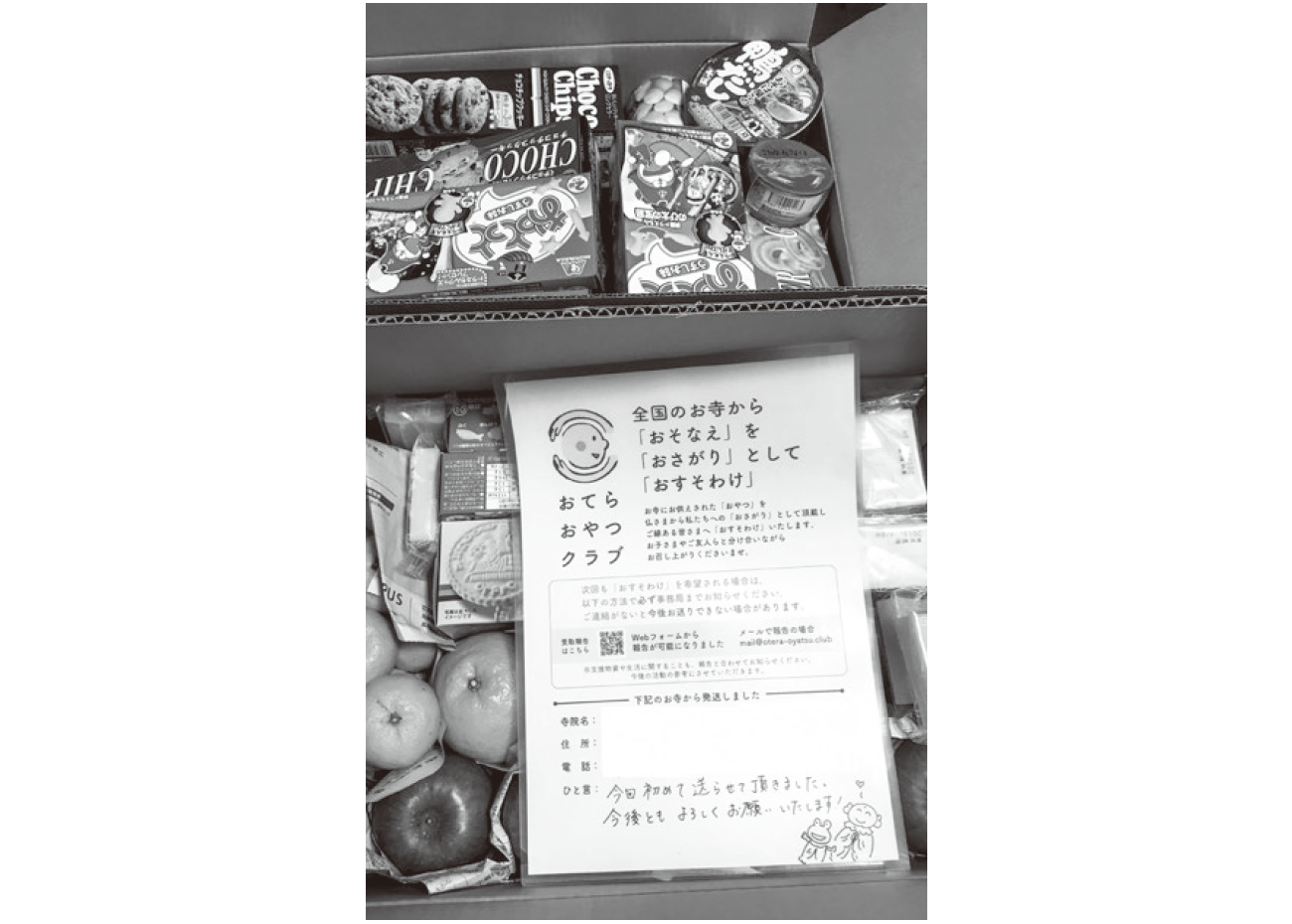

IT and many other technologies are now available to a broad range of people, which has lowered the barriers to creating new value. This is aptly demonstrated by the Good Design Grand Award winner, Otera oyatsu club. Years ago, it would not have been this easy to make progress in system-building (in this case, for a system to alleviate child poverty), which would have begun by looking for programmers to develop the system. The fact that priests aspired to create a platform uniting temples across Japan shows how technology has become an enabler that makes it easier to pursue solutions for our questions.

Another award winner, "Creccha," is a made-to-order service that creates stuffed toys closely resembling children's drawings. We can readily imagine how thrilled children must be to receive them. The service reminds us that creativity does not necessarily depend on how skilled one is at drawing. In showing the role of IT as an enabler that can inspire confidence and expand potential, this winning entry resembles Otera oyatsu club.

Thought processes as alternative techniques

Of course, there are technologies besides IT. In design, thought processes themselves can also be considered a key technology or technique. Creating new value in the world requires some kind of thought process. Knowledge about applying thought processes should probably be more widespread. The approach taken—how questions are framed, or how dialogue can be arranged for freer exchanges with others, for example—is emphasized in American design education.

In Japan, experience design has probably been fundamental throughout history. Imagine a visit to the Ise Grand Shrine. Any route taken is designed to converge with others at a bridge across the Isuzu River. It is as if the designers have placed us in a story that becomes more exciting as we approach the sanctuary. They seem to have had keen intuition and insight into human nature. In this way, the unwritten thought processes of old Japan were the stuff of legend, and they have created a treasure trove of Japanese heritage. Perhaps designers of today who apply them as a form of Japanese "design thinking" in new creations could make some exciting things.

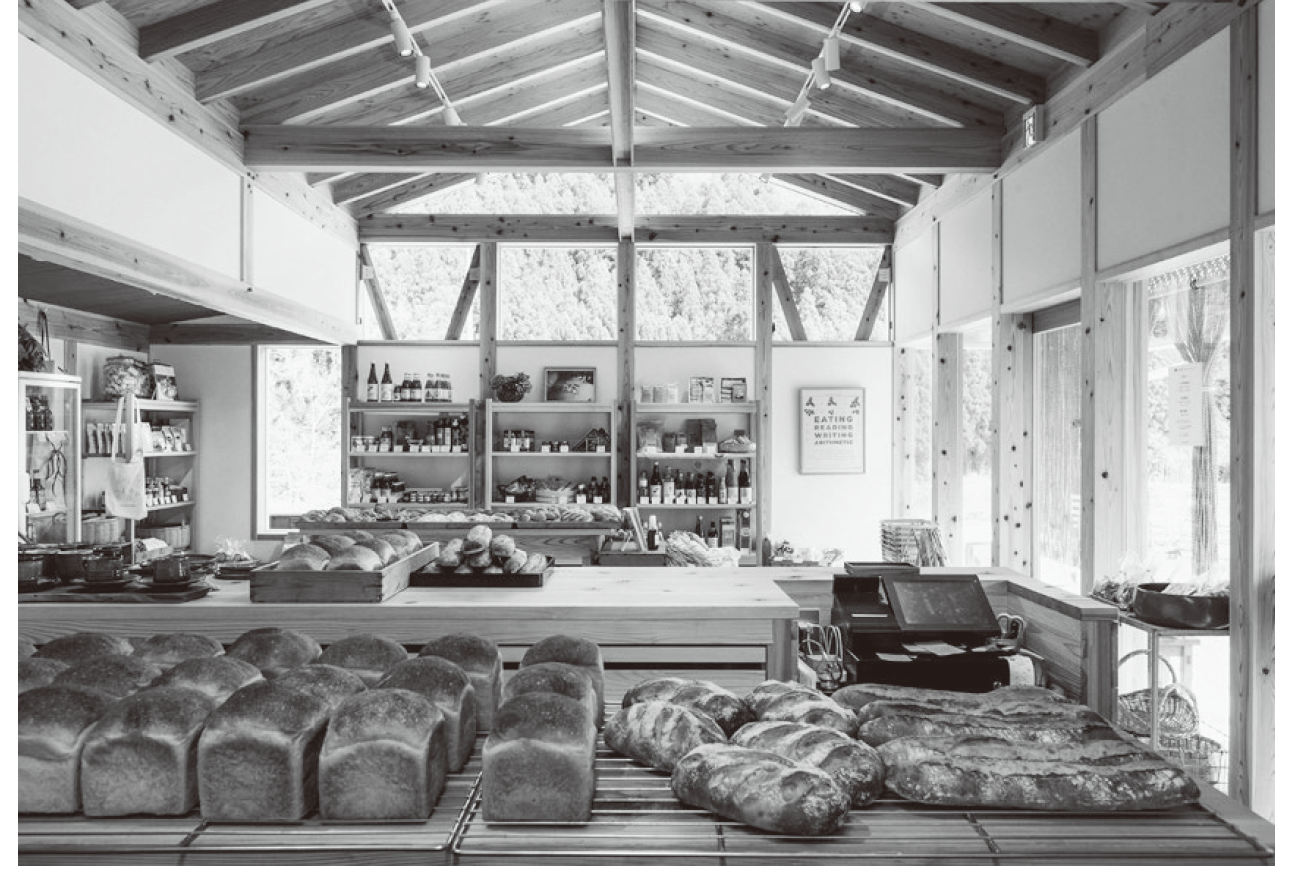

The award-winning Food Hub Project began with the question of how to take a Japanese approach to sustenance. It stands out admirably for establishing a cycle around this theme (cultivate, create, eat, and nurture) in a rural area and enriching life there. Here, we might describe the thought process itself as a new technique to help people lead happy lives. The same can be said for the award-winning hanare hotel concept. I hope to see these techniques shared effectively across society.

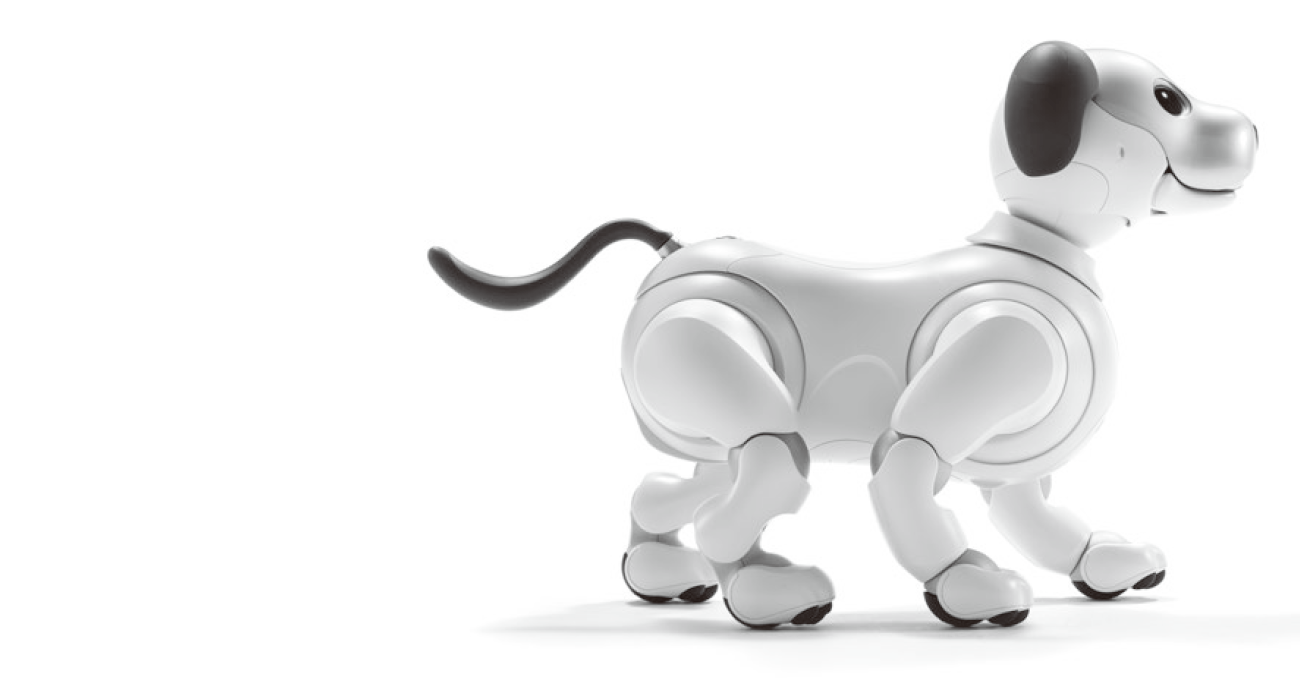

Among the year's award winners, one product that represents a certain view of our engagement with advanced technology is the aibo entertainment robot. Aibo is commendable for how its high-tech features (such as an array of sensors) bring to life the mannerisms of a pet dog. Even more outstanding achievements might be possible if products could somehow come with the context that accompanies real dogs, which we begin caring for while forming bonds of affection. How do we normally meet a new pet—packaged in a box? What if we could choose our new aibo from several, moving around freely? What if each aibo had different spots and coloring? And what kind of story would unfold if we could take home a "stray" aibo? Products developed by exploring these kinds of questions might positively reframe our engagement with technology.

Strategist / Managing Officer, Home Business, Airbnb Japan

Hidetomo Nagata

Envisioning welcome interaction between individuals and society

Essentially, how we work can be viewed as a matter of what style we adopt for the interactions between individuals and society—how we engage with each other.

In the context of work styles, this relationship between individuals and society has rapidly become more diverse and fluid than the dominant lifetime employment and seniority systems of a former age.

Not long ago, we would probably never have imagined that we would one day view affiliate marketing as a YouTuber or social media influencer to be a legitimate way to make a living and engage with society. We are constantly going through new ways of living and working, as a variety of work styles emerge and eventually decline in popularity.

But with ongoing debate on matters of work style reform or work-life balance inevitably revolving around time and money, based on traditional ways of working, one gets the impression that this talk is behind the times and the changes around us.

As many people and companies continue struggling to find ideal ways to work, what is needed may be the power of good design to suggest role models that demonstrate how the ties between individuals and society—the relationships we build—can bring us happiness.

Envisioning welcome interaction between individuals and society

Our evaluation of GDA entries this year revealed two directions taken in design-inspired attempts to change how we work.

One is the technology-driven acceleration of work style diversity. Dropbox Paper cloud services and the smart lock robot Akerun are elements of an infrastructure that supports cloud-based working styles. This kind of design can free people from having to work at a certain place or time.

Design that took another direction added breadth and strength to the ties between individuals and society, to enable sustainable growth of these ties.

By loosely weaving together vacant apartments, public baths, and other facilities in Yanaka, Tokyo, hanare expands the boundaries of a traditional hotel, which usually offers everything guests need (from check-in to dining to bathing) under one roof. This loose association also provides new forms of livelihood in the neighborhood.

Also exemplary was a project called Working Point, aimed at revitalization through multitasking. What makes this such a fresh idea is its approach to compensation. For the time employees spend working on behalf of other employees or departments, they are compensated by receiving time off work. Measuring these ties between individuals and society on a non-monetary basis strengthens them and suggests new possibilities.

Design of unseen values is changing how we work

To maintain strong ties between individuals and society as we expand boundaries, our various communities must also have some kind of narrative.

This kind of story inspired an award-winning brand of sake called X01, uniting agricultural equipment maker Yanmar, sake producer Sawanotsuru, and rice farmers from the stage of rice development for a new sake.

These contributors are at different positions in the agricultural value chain, but what motivated each of them to take a step forward together in this new venture was a shared appreciation of and commitment to writing a new chapter in Japanese rice farming and agriculture. The change in consciousness aroused by this empathy and commitment altered how the stakeholders worked, fostered interdisciplinary ties, and led to a new product.

Another key point plays a role in the kind of storytelling that changes the way we work: designing the unseen things that people value and believe in.

In traditional working arrangements, what people probably tend to value is visible and tangible, such as money or the number of hours worked. But when we take on new ties in the fabric of society, we are motivated by a sense of satisfaction, reassurance, achievement, or other values that are hard to visualize or verbalize.

Behind the mobile app CraftBank is a service that matches construction workers with companies looking for their skills. Besides the material conditions that make these matches feasible, such as hourly wages, the psychological need of being able to trust an unknown party must also be met. We look forward to seeing how the service fares in meeting these requirements and providing unseen value.

What things do we trust, and what things resonate with us? How do we wish to engage with society? And, knowing that what inspires trust also changes, as time flows, how can these arrangements be updated to keep pace?

What will drive changes in how we work and bring us happiness and fulfillment is dedication to constant design efforts focused on these unseen values.

Lawyer / CITY LIGHTS LAW

Tasuku Mizuno

Roles of AI in learning

Recent years have seen greater interest in two approaches to educational design for active learning. In one approach, ways of studying are expanded through e-learning and other applications of IT. In the other, learning opportunities are improved through the design of social environments, accounting for space, facilitation, and arrangements to serve students of all ages.

This year's award program also seems to have happened at a time when people began to realize how well artificial intelligence is suited to this active learning, now that AI-driven products and projects are materializing around us.

One award-winning tablet app called Qubena teaches math through adaptive learning. After AI is used to analyze areas where each student should improve, the app offers a personalized course of study. Another awarded mobile app, Japanese Language Training AI, provides a service to help people practice conversational Japanese. Thanks to a support AI developed for this purpose, the app not only helps users express themselves more freely, it gives tips on pronunciation and other ways to say things, for optimal communication. Both apps reflect a trend toward applying the information technology of AI in active learning.

Seeing opportunities to learn from the "other" of AI

As AI-driven products and services continue to spread, there is also greater interest in how AI can grasp things from perspectives we lack. According to thinker Kevin Kelly, this aspect of AI can define it not as an "artificial" intelligence but as an "alien" intelligence, which thinks about things differently, as if from another world. This view of AI invites us to use it not only as a form of information technology but also to provide an alternative, non-human perspective. Taking this view of AI makes us suspect that AI may be what teaches us the most, and that maximizing our learning from AI will be a priority in design.

From this standpoint, aibo has captivated many people. Each aibo keeps learning, through their connection to AI in the cloud. What impact will they have on us, or how will we influence each other? aibo itself interacts with owners, seemingly having wants and needs, as a creature that matures over time. One gets the distinct impression that especially with aibo, bonds may form between people and AI, in relationships that are interactive and meaningful. Although the outcome is yet to be seen, and further developments remain an unknown variable, if we can learn from aibo and grow together with it, this may be one indicator of our future relationships with AI.

As a more straightforward example, an NHK TV series has examined the AI perspective by asking an AI various questions about life in Japan to see what kinds of answers are offered, or if any can be offered at all. What is quite intriguing here is not evaluating the AI feedback (or lack thereof), after questions are posed and analyzed, but the approach of finding possibilities for cooperation with AI through this verification.

Through good design that explores these concepts in concrete ways, both award winners represent new attempts to emphasize positive outcomes from learning from AI, in a broad sense, and influencing each other.

Roles of design in AI

Clearly, cooperation between people and AI will be indispensable in addressing any of the significant issues faced by Japan, whether the low birthrate, graying society, declining population, or others. On the other hand, we can also view it as an advantage for Japan to take the initiative in dealing with the matter of AI relations.

In paving the way for AI in society, AI algorithm developers can be seen as designers, broadly defined. Careful UI and UX design is a facet of products and services that already apply AI, and professional designers sometimes contribute in these areas. But besides this, optimal applications of AI and our relationship with AI itself will probably be positioned as opportunities for good design. Here, a comprehensive approach to design will be essential, accounting for inherent risks of AI as well as ethics, rules, and laws on human dignity and the increasingly topical consideration of "well-being design."

Inclusivity is now a popular inspiration and approach in design, as we look for and address social issues through the eyes of those who are socially vulnerable or members of minority populations. In time, perhaps AI will also be considered an "other" through which to gain insight on social issues. People would benefit if collaborating and co-creating with AI provides active learning opportunities and serves as a source of expanded creativity. To me, this seems like a worthy goal for AI design.

Architect / OnDesign

Osamu Nishida

Valuable localities that satisfy our craving to belong

Quite a few people seem to have sensed the limits of driving the economy through cycles of mass production and mass consumption, as promoted in Japan for years. Even in the construction industry, there is a growing sentiment that with the population in decline, there is no need for more scrap-and-build than we already have, and that we need a new model, different from building something from nothing.

The old model is still alive and well in cities, however, so people looking for new fulfillment in life or meaningful values have turned to localities. This change represents a shift from being content to own land, possessions, or wealth to valuing community and other social capital, or building a life full of the nature and local culture of Japan, for example. A desire for possessions is never-ending. The moment we acquire the object of our desire, we start craving something new. Even if our quest for more can be satisfied under favorable economic conditions, this seems less likely at the present. In contrast, as we share life with other members of a community or area and pursue meaningful relationships, we find value in how these relationships endure over time. The more time we invest, the more valuable these ties become to us.

Many believe that localities are essential as a wellspring that helps to satisfy our desire for these relationships that bear fruit over time. Here and there, this thinking is already becoming established. Increasingly, we see examples of design which, in the spirit of nurturing localities, creates opportunities or arrangements to satisfy our desire for connectedness and weaves together enriching elements.

Localities spanning the urban and rural

One particularly intriguing award winner involving this kind of continuous cultivation is Food Hub Project. The project is organized in a few notable ways. Multiple initiatives and programs develop organically in a single area, unfolding at a rapid pace with ample opportunities to join in and be proactive. Also noteworthy is how it creates situations for nonresidents or urbanites to participate and be part of the community. Cities tend to homogenize diversity, but through each rural product made and story told in this outstanding project (which are brimming with local traditions and history), city dwellers are reminded of the significance and sustenance of localities and the richness of Japanese heritage.

Another award winner, hanare, is located in the older Yanaka area of Tokyo. Renovation for this hotel concept has skillfully preserved the venerable wood building, evoking a sense of the neighborhood and the passing of time. Here, shared values are maintained between the hotel and existing public baths, delicatessens, and other businesses nearby, enabling effective outsourcing of hotel functions. Walking around Yanaka, guests may even get the impression that the whole town is at their service. Another award-winning hotel that promotes locality is OMO5 Tokyo Otsuka, which offers tours by community members and sightseeing influenced by local perspectives.

Both examples of design expand guest services, but this is less to satisfy a desire for possessions than one for connectedness. Both blur traditional boundaries between the hotel and the neighborhood. By arranging for local businesses to share the roles of the hotel, and by nurturing these ties, the hotel fosters a sense of belonging that makes accommodations more pleasant while keeping a watchful eye on local changes and growth. Still, although the proprietor may feel that their hotel is a local institution, there is no need to engage with all nearby businesses. The key is probably to keep an open mind and support the autonomy of guests of all kinds through fuller services.

In this sense of designing an open-minded arrangement where one can determine the extent of ties with others, an award-winning Kissa Laundry stands out for having created a place that patrons appreciate visiting repeatedly to mingle. As design that in effect lets us discover things on our own terms, it encourages a kind of locality for our times.

Another notable award winner addressing locality from a somewhat different perspective is Gogoro. In this approach to solving urban problems, all elements of the system are quite well-designed. Yet this design itself is not emphasized, and as a result, the platform in place promotes the user experience and allows users to decide for themselves how the platform fits in their life. Thanks to expert use of IT, Gogoro is also flexible and can be adapted to a variety of localities. As systems and an array of services are expanded, it may continue to grow across borders.

Insightful and connective business operationsconnective business operations

In architecture, most urban planning and large-scale construction has been driven mainly by developers, and the desire for possessions has figured prominently in their thinking. However, in a growing number of cases, participants focused on the character of cities or on a desire for connectedness have played a greater role. Already, we are beginning to see the possibility of new cities being built under the guidance of companies such as WeWork or Airbnb, whose business models emphasizes social capital. As good design is employed to plan new experiences that yield deeper insight from traditional sources of knowledge (such as lifestyles, local culture, and established practices) while responding to emerging values of our era, it will no doubt be linked to enhancing localities.

Project Manager / CEO, Quantum\Global

Yuta Inoue

Understanding three phases of social infrastructure

The supportive role of social infrastructure is clear from infra- (meaning "below" or "beneath"), and this narrow, traditional sense of the expression may call to mind structures such as bridges or train systems. More advanced infrastructure raises standards of living, and at another key stage, these arrangements keep society and everyday life running smoothly, but each phase is intended to benefit society as a whole.

Social infrastructure that is both practical and beautiful

In traditional social infrastructure, we find exemplary architectural, spatial, and signage design at the Group 7 facility of the Nishi-Nagoya Thermal Power Station. Other power plants or facilities that were engineered or designed mainly by focusing on their functions as machines have faced some problems. To workers, they are inconvenient, and errors are more likely to occur. More pleasant, convenient facilities can be created by taking an approach common at public transit stations, for example, where designers pay close attention not only to the use of space but to color schemes and signage, which may also inspire a greater sense of pride and belonging among workers.

In soft social infrastructure, one award-winning Kissa Laundry seems to epitomize this kind of infrastructure. It is as if a company has opened its office to the public, creating infrastructure resembling a private community center. The role it fulfills is not too different from that of government offices of a bygone era, so it is only fitting that the patrons themselves are largely responsible for organizing the 500 or so events held here each year.

Similarly, Otera oyatsu club taps the practical infrastructure provided by a network of established temples across Japan to take on a social issue that should be addressed by public policy on family poverty. Although it is the philosophy behind the program that tends to capture people's interest, jury members no doubt appreciated the idea of linking intermediaries in this unique network, as well as the skillful supply chain operations and community management applied to collect and distribute offerings. The program has attracted attention elsewhere in Asia, which raises the prospect of forming global infrastructure.

Also commendable is how an app called Nigetore serves as a form of infrastructure. The service provided by the app shows evacuation routes for large earthquakes and tsunami near the Nankai Trough. Based on estimates of tsunami flooding, the app also shows the user's progress as they practice evacuating. During the Tohoku disaster, some older students who had participated in routine evacuation drills could lead younger students to safety, and community members who saw this were also able to escape. People were once guided by warnings from older generations as inscribed on stone monuments, but these monuments tend to fade from the landscape and lose their significance over time. This modern design achievement gave me the impression that apps can replace such monuments for use in drills or actual evacuation.

NarrativeBook in Akita is another award winner that holds potential as a new form of infrastructure. Unlike most medical records that are merely efficient chronicles of patient history, these records tell a fuller story through additional, personal accounts given by the patients themselves or their caregivers, which may facilitate needed treatment and improve the quality of care.

Thus, it seems significant that we find both practical and emotionally engaging design elements in each of these impressive winners this year.

Meeting needs for a human approach

Looking ahead, I think people will gain an appreciation for things with a sense of humanity—qualities that emphasize the human. When we consider technological startup projects involving online services, apps, or hardware, it seems that those developed with the human dimension firmly in mind find widespread support sooner and ultimately become more popular.

The Gogoro Energy and Transportation Platform demonstrates this well. Working backwards from the goal of solving the problem of global air pollution, the developers thoroughly considered the time needed to give users a pleasant or exciting experience—just a 0.3-second initial encounter with their iconic electric scooter, a 3-second glance in person at a showroom, 3 minutes trying out the app, and 3 days of riding before switching to a charged battery. How each of these scenes has been carefully framed to advance customer communication is impressive. The platform has become established in society at a scale quite in line with users—the human dimension so carefully considered in development. In this respect, we might call the Gogoro platform a perfect example of infrastructure for a new era.

Especially when we want to shift the perspective from Is this a viable business or enterprise? to How can we gather the resources to solve this problem?, good design can be effective. Now that a broader understanding is called for—to the extent that design also encompasses delivering goods or services precisely the right way, or maximizing their sense of purpose—it is more important to realize that besides individual designers, participants of all kinds help build social infrastructure that brings happiness to people.

Architect, Designer / CEO, Keiji Ashizawa Design, Ishinomaki Laboratory

Keiji Ashizawa

Things that enrich moments of life

The value of everyday life is enriched through the activity of design, and this year's Good Design Award program showed attempts to do this in many different fields. Each year, well over a thousand entries are recognized with an award. All the individual products, buildings, services, arrangements, and other entries represent elements of society as a whole, which gives one the impression that from this undercurrent, our quality of life is being enhanced.

The things that contribute to quality of life are not extravagant. Good examples are the familiar, everyday things we can rely on to make life better. In Sweden, a friendly coffee break called a fika draws people together, even at work, for a chat and a snack. A fika is not fancy, but anyone might enjoy this chance to mingle. Thus, a suitable tray for the sweets can be viewed as emblematic of a good life. Even if these tangibles or intangibles are not so special, they do make life a little better.

In this sense, award-winning TouchFocus glasses seemed quite meaningful to me. As a new form of bifocals, they change strength at the touch of a button on the frame. For those old enough to worry about being farsighted, TouchFocus eliminates the need to switch glasses, and it is appealing that the interface makes them second nature to use, so there is no need to be self-conscious. This regard for users addresses people's resistance to reading glasses by imagining a world where instead of retiring to private pursuits, these older users remain active and engaged with others of all ages. What has set the scene for such products are the longer lifespans and increasing number of seniors in Japan, but more than merely supporting these users, the glasses tap human mannerisms and a sense of fashion to create new value. The approach suggests how society can be more broad-minded and have our quality of life improved by good design, little by little.

Urban development improving quality of life

Another award winner explores this topic on a larger scale, by establishing a temporary neighborhood hub. Design in this program boldly opens up areas usually walled off during the construction of residential complexes and invites the community in. Besides setting up outdoor furniture and equipment for people to use, the developers encouraged participation by a local university, businesses, and other community groups, meeting both "hard" and "soft" needs. The project was planned with input from architects, which probably helped the developers cover all aspects from structures to finer details. Also quite interesting is how a leading general construction company with ample experience in real estate development shared this narrative with the architects. One senses that the project may represent a turning point for our times.

Judging from this project, we can discern how a shift from economic value to quality of life is grounded in real-world considerations not only for users but also for businesses. Beyond seeking taller and more value-added buildings, as Japan's population continues to decline, we should probably be seeking more points of contact with communities. Ideally, those involved should take a stance of using what was developed for the temporary neighborhood hub project at the next site, and applying it in other development.

In other award-winning design—a Kissa Laundry and the hotel concept hanare—we see perfect examples of how quality of life can be created by engaging with communities through architectural approaches. The Kissa Laundry washing machines, a kitchen, and a café area, all devised to enliven this ground-level, neighborhood-accessible space. hanare in Yanaka, Tokyo, provides accommodations by combining multiple sites, as if the entire district were part of the hotel. Both are certainly examples of design intended to create new value in our life by addressing remarkable changes in cities over recent years, as apartment buildings keep popping up and the population swells amid thriving inbound tourism.

These success stories should not be viewed as sudden, random instances. Instead, they should endure, grow, and spread as sustained activities, because both hold potential as exemplary ways for communities to prosper.

Quality of life from public resources

Another memorable arrangement that can improve quality of life is Otera oyatsu club. Though some may be startled by how this Good Design Grand Award winner raises a social issue, I sensed possibilities in how the program has focused on fulfilling a new role through the existing infrastructure of temples across Japan.

From the same perspective, we may find a viable approach to addressing the problem of food waste, for example, through a solution that diverges from the usual business of convenience stores—a form of infrastructure that distributes much food each day. Facilities such as subway stations may also be capable of a variety of additional new roles besides their current ones, in consideration of the locations of this infrastructure, which is so prevalent in cities. In this way, Otera oyatsu club suggests that by reinterpreting familiar situations or facilities in our life as potential public resources, we may discover something that can contribute to improving or ensuring quality of life.

It is worth noting that Otera oyatsu club began with the efforts of a single temple. What started small, as one temple relying on themselves for the initiative, now continues to create broader waves through ties with other supportive temples and local charities, as it reaches people through social media and other means. We have seen that one person's inspiration or vision can, while applying a variety of existing infrastructure, provide a public resource. To me, this is a solid value in our lives today.

Design Strategist / Founder, Nosigner

Eisuke Tachikawa

The stakeholders left behind

In teaching my approach of evolutionary thinking, which contrasts design with biological evolution, I often make comparisons and observations about ecosystems and society. A point emphasized in this context is the state of symbiosis, or coexistence. The word symbiosis (and its Japanese equivalent, kyosei) is now used in many situations, but it was originally a specialized term in biology. Clownfish and sea anemones enjoy a symbiotic relationship, for instance, as different species living together with shared interests. Symbiotic relationships can be cooperative (mutualistic), competitive, or otherwise. To understand how to observe such biological relationships, I think it is directly applicable to observe stakeholders in a corporate relationship. Corporate marketing usually only shows the role of consumers, but there are stakeholders in a broader symbiotic relationship.

In a traditional consumer society, too few stakeholders are accounted for. For example, subcontractors whose costs are considered excessive and quality inferior cannot build ties with manufacturers and are left behind. Other problems may occur if the things consumers purchase are soon discarded, which has an environmental impact over time that may lead to others being disadvantaged by this relationship. Neither should we overlook the existence of those without access to beneficial technology, or those who fall outside of market standards.

Fewer people survive when the competitive relationships of a consumer society intensify. Instead of this, finding value in the stakeholders left behind or somehow saving them can be described as a key theme in business and contemporary society at large. In other words, only by rebuilding traditional relationships and considering arrangements where a variety of stakeholders support each other can we take on design for a society in mutualistic symbiosis.

Many approaches to designing a society in symbiosis

Otera oyatsu club represents design that finds neglected stakeholders, seeks to reframe relationships, and turns something familiar into something valuable in new ways. It is the design of an arrangement, without a definite physical form, that redistributes temple offerings to families in need, which in Japan exceeds 100,000 households. This relationship may seem one-sided, but it is not, because families in need offer thanks and prayers in return, which in a sense helps the temples spread their faith. This moving narrative struck a chord with many jury members: Temples have served as hubs of the community for 1,500 years, and here, they are tapping the value of their unique relationships to build an ecosystem with poor families left behind by society.

Another project representing society in symbiosis is the Gogoro. Electric vehicle batteries are shared as social infrastructure, and sustainability is supported. The project envisions a symbiotic relationship with quite a broad range of stakeholders. To provide batteries, stations under direct management coexist with stations outsourced to convenience stores. In this way, companies that might otherwise be competitors cooperate on the same energy platform. Moreover, this system is offered under a clear vision of eliminating pollution and creating sustainability in the world.

Similarly, the hanare hotel concept has discovered the value of turning vacant apartments into guest rooms. It is a wonderful case of creating symbiosis in a veritable citywide hotel. We can admire how hanare maintains ties with other stakeholders, such as local public baths and restaurants, which shows quite well how to establish a symbiotic relationship.

Also significant is how renovation by a waterfront park called tocotocodandan linked embankment work (for flood control and disaster preparedness) to the creation of a promenade for people to enjoy the river. It gave me a sense of hope to see how an area that had been left behind has been transformed into a place that the community will be glad to discover and have in their life. In these ways, design for a society in symbiosis seemed like a key theme in this year's Good Design Award program.

The power of design to meet future needs

Recent years have seen growing interest in the U.N.'s global sustainable development goals, or SDGs. Besides establishing 17 goals (such as "No poverty" and "Zero hunger") and 169 relevant targets, the U.N. has promoted symbiosis in society by stating that no one should be left behind. Many people are beginning to notice the risks posed by societies that are merely competitive and offer no vision for potentially symbiotic ecosystems.

It was immediately after the two world wars of the 20th century that design flourished, during the Mid-Century Modern movement. Good design no doubt fulfilled a vital role in rebuilding societies ravaged by war. But over time, more specialized and narrow matters of design diverged from social concerns, as design split into specializations. Design is good at narrowing things down, and indeed, we can say that those working in design readily spent much time doing this. But in Japan, especially in response to the Tohoku disaster, besides developing new things, we should leverage strengths to compensate for the weaknesses of existing things. We are recognizing once again that good design makes it possible to invent new symbiotic relationships in society. Now that design is no longer the exclusive domain of professional designers, will we share an attitude of finding ways to encourage the symbiotic relationships increasingly needed to take shape in the world?

Seirou Matsushima, Ryoo Fukui / Otera Oyatsu Club

Otera oyatsu club is a nationwide program run by a nonprofit organization that redistributes temple offerings to children in single-parent families. Many such families live in poverty, and because temples receive considerable amounts of food and snacks as offerings, this distribution represents a solution for temples and children alike.

Temples and children's charities are invited to register in the program and matched geographically by the nonprofit. The temples then send the food to nearby charities, which in turn distribute it to families. Even temples that do not receive many offerings can participate, because the deliveries can also be sent monthly or only on holidays, and multiple temples can pool their offerings. Crucially, the program is open and easy for many people to join.

Also significant is the fact that the program is run by a nonprofit, which avoids common preconceptions about religion and enables participation by municipalities and corporations that cannot support religious organizations. Of Japan's nearly 70,000 temples, about 1,100 have joined the program so far. In time, we would like the program to make a difference in alleviating poverty.

Otera oyatsu club is not sustainable without offerings to temples. Those of us who follow Buddhism at temples, where the Buddha is central, must also ensure that we are worthy of receiving these offerings.

The human-centered approach extolled in design remains short-sighted, and we cannot get past the limitations of human lifespans and thinking. It is important to pass down to the future our Buddha-focused heritage from antiquity, and we must also consider and do what we can for those living today.

Mitsuyoshi Miyazakii / HAGI STUDIO Inc.

HAGISO in Yanaka, Tokyo, houses a café and exhibition space, as the smallest of cultural centers. My background is in architecture, but I have managed the building since 2013. Although HAGISO draws many visitors, this is ensured by the charming district of Yanaka itself, so turning the area at large into a hotel to offer an authentic local experience over a day-long stay is what the hanare concept is all about.

After guests check in at HAGISO, they learn about bathing at a public bath and dining at nearby restaurants. This is a wooden building, more than 60 years old, and the fact that it was so ordinary gave us freedom in renovation.

We hope hanare changes how guests see the district. Changing people's awareness through the design of facilities, services, and the like may discourage efforts to "clean up" neighborhoods, which is a factor of unwanted gentrification. In regulating the flow of people in an area, inns have a role to play. Essential considerations include what demographic the district welcomes, how guests should conduct themselves, what they gain from their stay, and how they feel on departure.

Drawing on what I learned from hanare, I founded the Japan Machiyado Association, which encourages inns to develop close community ties, and ties to other such inns. We want to connect inns across Japan who believe that accommodations should be citywide in scope. By tapping local resources, even hotels without any special technology or facilities can offer guests a memorable stay, which will probably also please the community. What keeps us interested in hanare operations is the fascinating nature of this work. As we enjoy ourselves doing what we can, if it ends up helping people, then that would make us happy.

Noriaki Takagi, Toru Kurata, Junichiro Sakata / Sony Corporation

After years of technological innovation since the first generation of AIBO was released in 1999, development of the new aibo began by focusing on vitality. It was agreed that aibo would be an object of affection, instead of anything strictly practical. Most of all, the design must somehow bring to life a creature that now has its own desires and can express itself through tricks and gestures.

The kind of character sought in aibo would make owners want to pet and hold it. Despite the plastic materials used, aibo would seem soft. The OLED eyes are quite expressive and natural-looking. As for how aibo moves, this was inspired by a wholly new UX approach. We took a cue from how real dogs express themselves, which is why aibo can interact with people so well.

Aibo applies AI in a range of perceptions, processing, and actions, which guides its behavior. Moreover, each aibo has a different personality, and as an autonomous creature, each develops in various ways over time. A priority in this respect was having new stories unfold between aibo and people. These relationships were carefully studied by our design team, who imagined how owners would feel. In our awareness of relationships between physical things and users, product development was quite different this time.

The future we hope to trace out is one where people's lives are enriched by the AI and robots they spend time with, and where this coexistence makes the world a more peaceful place. Nothing would make us happier than for people to say it all started with aibo. That is exactly the role Sony should fulfill.

Taichi Manabe / Food Hub Project Inc.

As a corporation formed in 2016 by the town hall, farmers, local businesses, and other stakeholders of rural Kamiyama, Tokushima, Food Hub Project passes down regional agricultural and culinary traditions to the next generation. One virtuous cycle established by the project can be found at the restaurant-bakery, which serves the community meals made with produce from other project participants in the spirit of local production for local consumption. Before the project began, a working group met in 2015, vowing to stand together as a team that would forgo excessive consensus-building, take risks, and not be deterred by criticism.

Love of community helps establish sustainable food practices. To encourage this, the project has emphasized aesthetics over economics and local perspectives over external ones, while showing an appreciation for everyday life and those who make it possible. What gives the project momentum is that members value continuous improvement, rather than creating something from nothing. Creative work in this approach focuses on things that set this region apart.

In response to widespread requests to participate in Food Hub Project, methods and ideas are suggested after consulting chefs in a chef-in-residence program. The program has had tangible results, as seen in requests for store concept-building and product development.

Our project gives back to the community by simultaneously supporting farming, running a restaurant-bakery, developing packaged products, and teaching culinary heritage. This work is done as a team. Delicious meals are essential to food projects, but good design can arouse many people's imaginations and make them crave a beautiful food culture and growing regions behind it.

Interview / Writing

Aya Ogawa(Director Message 1,2,3,4,5,7 and Food Hub Project)

Takahiro Tsuchida(Director Message 6, Otera oyatsu club, hanare and aibo)